History isn’t just dates and dead presidents, it’s the messy, fascinating, often surprising story of how a collection of rebellious colonies became the complex nation we know today. While most people think American history means a quick tour of Washington D.C. monuments, the real stories live in places where you can walk the same streets as founding fathers, stand in rooms where the Constitution was debated, and touch the walls that witnessed America’s most defining moments.

These aren’t sterile museums or sanitized tourist attractions. They’re places where history happened, where you can feel the weight of decisions that shaped a continent, where the echoes of past voices still resonate in preserved buildings, and where the American experiment reveals its full complexity through layers of triumph, tragedy, and transformation.

From revolutionary battlefields where farmers defeated the world’s greatest army to Civil War sites where the nation nearly destroyed itself, from indigenous settlements that predate European arrival by centuries to immigrant neighborhoods that redefined what it means to be American, these destinations prove that history isn’t ancient. It’s alive, it’s everywhere, and it’s waiting for curious travelers who want to understand how we got here.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia doesn’t just claim to be America’s birthplace, it actually is. Independence Hall stands as the room where delegates spent a sweltering summer of 1776 debating whether to commit treason against King George III, then returned 11 years later to create the Constitution that still governs us today. You can stand in the actual room where John Hancock made his signature large enough “for the King to read without his spectacles,” and where Benjamin Franklin warned that they’d created “a republic, if you can keep it.”

The Liberty Bell’s famous crack tells its own story of American imperfection, a symbol of freedom that was literally broken, much like the nation it represents. But Philadelphia’s historical depth extends far beyond the obvious sites. Elfreth’s Alley, America’s oldest continuously inhabited residential street, shows how ordinary colonists lived, while the Museum of the American Revolution reveals how a rag-tag collection of farmers defeated the world’s most powerful empire.

Christ Church Burial Ground, where Benjamin Franklin, four other signers of the Declaration of Independence, and five signers of the Constitution are buried. Visitors still throw pennies on Franklin’s grave for good luck.

Independence Hall tours are limited and timed, but standing in that room during late afternoon light, when shadows fall across the same chairs where history’s most important debates occurred, creates an almost mystical connection to America’s founding generation.

Williamsburg, Virginia

Colonial Williamsburg represents the most ambitious historical recreation in America, an entire 18th-century city where costumed interpreters don’t just wear period clothing but embody the mindsets, conflicts, and daily realities of colonial life. This isn’t entertainment disguised as education; it’s serious historical immersion where blacksmiths forge real horseshoes, where tavern keepers serve dishes from 300-year-old recipes, and where political debates reflect the real tensions that led to revolution.

The reconstructed colonial capitol building is where Virginia’s House of Burgesses developed many ideas that became foundational to American democracy. Patrick Henry’s famous “liberty or death” speech echoed through these halls, while Thomas Jefferson served his political apprenticeship in rooms you can still visit.

The interpreters spend years researching their characters, real historical figures, and stay in character while discussing everything from politics to personal beliefs. You might debate the merits of revolution with someone portraying a loyalist shopkeeper or discuss slavery’s contradictions with someone representing a plantation owner.

The Governor’s Palace showcases royal authority that colonists ultimately rejected, while the Capitol demonstrates how Virginia’s planter aristocrats developed democratic ideas that challenged monarchical power.

Boston, Massachusetts

Boston wears its revolutionary credentials proudly, this is where “taxation without representation” transformed from slogan to revolution. The Freedom Trail connects 16 historically significant sites across 2.5 miles of downtown walking, but Boston’s historical importance extends far beyond revolutionary tourist spots.

Faneuil Hall earned the nickname “Cradle of Liberty” as the meeting place where colonists planned resistance to British policies. The Old North Church’s “one if by land, two if by sea” signal launched Paul Revere’s midnight ride, while the site of the Boston Massacre marks where tension between colonists and British soldiers erupted into the violence that helped justify revolution.

Harvard University, founded in 1636, represents America’s oldest institution of higher learning, while the Boston Public Library became America’s first large municipal library free to all citizens, both institutions that shaped American intellectual culture.

Walking the Freedom Trail during early morning hours, when crowds are minimal and light reflects off 18th-century buildings, creates genuine connection to the colonial city where revolution began.

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Gettysburg National Military Park preserves the battlefield where America’s bloodiest war reached its turning point. Over three days in July 1863, Union and Confederate armies fought battles that killed or wounded 50,000 Americans, more casualties than any other battle in the Western Hemisphere. But Gettysburg’s significance extends beyond military strategy to the fundamental question of what America would become.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered just four months after the battle, redefined American purpose in just 272 words. Standing at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery where Lincoln spoke, you can contemplate how this brief speech transformed a war to preserve the Union into a crusade for human equality and democratic ideals.

The park’s auto tour covers key battle sites, but walking specific areas—like Pickett’s Charge route or Little Round Top, provides visceral understanding of terrain that determined battle outcomes and, ultimately, American history.

The Gettysburg Address Memorial marks the spot where Lincoln delivered words that redefined American democracy, transforming a battlefield dedication into a statement of national purpose that still resonates today.

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe tells America’s most complex cultural story, a place where Pueblo peoples, Spanish conquistadors, Mexican settlers, and American pioneers created a unique blend that predates Plymouth Rock by a decade. The Palace of Governors, built in 1610, served as the seat of government under four different flags and remains America’s oldest continuously occupied public building.

The Plaza has witnessed public executions, religious processions, military occupations, and cultural celebrations for over 400 years. Today, Native American artisans sell jewelry and pottery under the Palace of Governors’ portal, continuing traditions that connect directly to pre-Columbian cultures while adapting to contemporary economic realities.

Santa Fe’s history challenges simple narratives about American expansion and cultural development. The city’s architecture, cuisine, and artistic traditions reflect continuous cultural negotiation rather than simple conquest or replacement.

Many cultural practices visible today, from Pueblo feast days to Hispanic religious observances, represent unbroken connections to historical communities that preceded American statehood by centuries.

Washington, D.C.

Washington D.C. functions as America’s national memory, where monuments and museums preserve stories that define national identity. The National Mall creates a visual narrative of American history from the Capitol Building (where laws are made) to the Lincoln Memorial (where ideals are remembered), with the Washington Monument serving as the central axis around which American memory revolves.

The Smithsonian Institution’s 19 museums contain the physical artifacts of American experience, from the original Star-Spangled Banner to Dorothy’s ruby slippers, from the Wright brothers’ airplane to pieces of the Berlin Wall. These aren’t just objects but tangible connections to moments that shaped American culture.

Each memorial tells specific stories while contributing to broader narratives about American values, sacrifices, and aspirations. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial’s reflective black granite creates emotional experiences that transcend political divisions, while the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial places civil rights struggles within the broader context of American democratic evolution.

Unlike historical sites that preserve past events, Washington D.C. offers opportunities to witness democracy in action—Supreme Court arguments, congressional hearings, and political demonstrations that continue the American experiment in self-governance.

Savannah, Georgia

Savannah survived the Civil War largely intact, creating one of America’s largest collections of antebellum architecture and urban planning. The city’s 24 historic squares, laid out in the 1730s, demonstrate innovative urban design that influenced American city planning, while the preserved buildings tell complex stories about wealth, slavery, and Southern culture.

Savannah’s historical narrative encompasses both the elegant mansion tours that celebrate architectural achievement and the painful realities of the slave labor that created such wealth. The First African Baptist Church, founded in 1773, represents one of America’s oldest Black congregations, while the nearby slave markets remind visitors of the economic foundations that supported Savannah’s antebellum prosperity.

Savannah’s Historic District contains one of the largest collections of restored 18th and 19th-century buildings in America, providing immersive experiences of how wealthy Southerners lived before the Civil War.

Modern interpretation addresses both the architectural beauty and the moral contradictions of antebellum culture, helping visitors understand how prosperity and oppression coexisted in pre-war Southern society.

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston embodies America’s founding contradictions, a city that created architectural beauty and cultural sophistication built on the foundation of human bondage. The city’s historic district preserves antebellum mansions and gardens that showcase the wealth generated by rice and cotton plantations, while sites like the Old Slave Mart Museum confront the brutal realities that made such prosperity possible.

Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, marks where the Civil War began when Confederate forces fired on federal troops in April 1861. The fort now serves as a National Monument where visitors can contemplate how political disagreements about slavery’s expansion led to armed conflict that killed 600,000 Americans.

Charleston’s famed cuisine, architecture, and hospitality traditions reflect African, Caribbean, and European influences that developed through centuries of cultural interaction, often forced and traumatic, but ultimately creative.

Recent efforts to acknowledge slavery’s central role in Charleston’s development include the International African American Museum, which examines how enslaved Africans and their descendants shaped American culture.

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

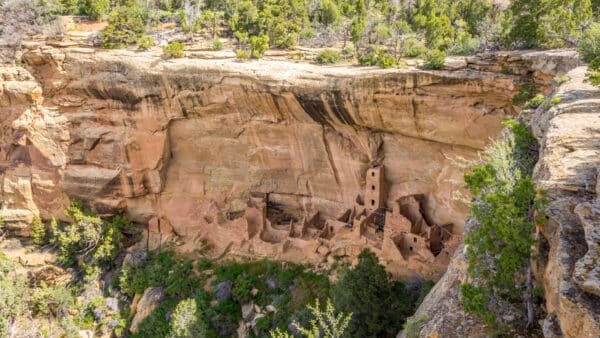

Mesa Verde preserves over 5,000 archaeological sites, including 600 spectacular cliff dwellings built by Ancestral Puebloan peoples between 600 and 1300 CE. These sophisticated settlements, built into canyon walls and featuring multi-story buildings, ceremonial chambers, and complex water management systems, demonstrate advanced architectural and engineering skills that challenge stereotypes about pre-Columbian American societies.

The Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde’s largest cliff dwelling, contained 150 rooms and housed approximately 100 people. Walking through these ancient buildings provides direct connection to American civilizations that developed independently from European influences, offering perspectives on American history that extend far beyond the traditional colonial narrative.

Mesa Verde represents the most complete preservation of Ancestral Puebloan culture, allowing visitors to understand how sophisticated American societies developed architectural, agricultural, and artistic traditions centuries before European contact.

Modern Pueblo peoples maintain spiritual and cultural connections to Mesa Verde, providing contemporary interpretation of ancient sites and demonstrating how indigenous cultures continue to evolve while maintaining essential connections to ancestral traditions.

New York City

New York City tells the story of how America transformed from a collection of English colonies into a multicultural democracy. Ellis Island processed 12 million immigrants between 1892 and 1954, making it the gateway through which one-third of current Americans can trace their ancestry. The immigration museum preserves the experience of arrival, the medical examinations, legal interviews, and emotional reunions that defined the American dream for millions of families.

The Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side shows how immigrant families actually lived, worked, and adapted to American life. These preserved apartments reveal both the hardships and the hopes that characterized the immigrant experience, while demonstrating how different ethnic communities maintained cultural traditions while becoming American.

New York’s neighborhoods tell stories of how successive waves of immigrants: Irish, German, Italian, Jewish, Chinese, Puerto Rican, and many others, created the ethnic diversity that redefined American identity.

From Washington’s inauguration at Federal Hall to contemporary political protests in Times Square, New York has served as a stage for American democracy’s most important moments and ongoing debates.

Cahokia, Illinois

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site preserves the remains of the most sophisticated pre-Columbian settlement in North America. Between 1050 and 1200 CE, this Mississippian culture city housed 10,000-20,000 people, making it larger than London at the time. The massive earthen mounds, including Monks Mound, which rises 100 feet and covers 14 acres, demonstrate engineering capabilities that required complex social organization and sophisticated understanding of engineering principles.

Cahokia challenges assumptions about pre-Columbian American societies by revealing evidence of urban planning, social stratification, long-distance trade networks, and astronomical knowledge that supported a complex civilization. The site helps visitors understand that American history includes sophisticated societies that developed independently from European influences.

Archaeological evidence reveals planned plazas, residential districts, craft specialization, and monumental architecture that demonstrate advanced urban civilization centuries before European contact.

Cahokia’s decline around 1400 CE, likely due to environmental pressures and social changes, provides lessons about how civilizations adapt to changing conditions and how human societies can both create and abandon sophisticated urban centers.

Pearl Harbor, Hawaii

Pearl Harbor represents America’s sudden transition from isolationist democracy to global superpower. The December 7, 1941 attack killed 2,400 Americans and destroyed much of the Pacific Fleet, but it also unified American public opinion behind entering World War II and accepting America’s role as a global democratic leader.

The USS Arizona Memorial, built over the sunken battleship where 1,177 sailors died, creates powerful emotional connections to the human cost of America’s global responsibilities. Oil still seeps from the Arizona’s fuel tanks, creating a visible reminder of that day’s impact on American history and international relations.

Pearl Harbor marks the moment when America abandoned isolationism and accepted responsibility for defending democracy worldwide, a role that has defined American foreign policy ever since.

The memorial combines historical education with emotional tribute, helping visitors understand both the specific events of December 7, 1941, and the broader implications for America’s role in the world.

Selma, Alabama

Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge stands as the site where American democracy faced a crucial test on March 7, 1965. When peaceful voting rights marchers were beaten by state troopers on “Bloody Sunday,” television coverage of the violence shocked the nation and created overwhelming support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Walking across the bridge today, visitors can contemplate how far America has traveled from its founding promise that “all men are created equal” to actually ensuring that all citizens can exercise democratic rights. The National Voting Rights Museum tells stories of courage, sacrifice, and determination that extended democratic participation to Americans who had been excluded since the end of Reconstruction.

Selma represents the culmination of a century-long struggle to fulfill the democratic promises made during Reconstruction but abandoned in the 1870s, demonstrating how democracy requires constant vigilance and continuous expansion.

Ongoing debates about voting rights make Selma’s history particularly relevant to contemporary discussions about democratic participation and civic equality.

Little Bighorn Battlefield, Montana

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument preserves the site where Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and 210 soldiers of the 7th Cavalry died fighting Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors on June 25, 1876. But the site tells more complex stories than the traditional “Custer’s Last Stand” narrative, it explores how American westward expansion conflicted with indigenous peoples’ rights to their ancestral lands.

The battlefield interpretation has evolved to include Native American perspectives on the battle and its meaning. Markers show where individual soldiers fell, but the site also honors the Native American warriors who defended their families and traditional ways of life against an expanding American nation that viewed their lands as empty territory waiting for settlement.

Modern interpretation presents the battle from both U.S. military and Native American viewpoints, helping visitors understand how different cultures interpreted the same events and how historical narratives reflect the perspectives of those who tell them.

Little Bighorn represents the violent collision between American expansion and indigenous resistance, forcing visitors to grapple with the moral complexities of how the United States acquired the territory that became the western states.

Planning Your Historical Journey

American history lives in these places, waiting for visitors curious enough to move beyond simplified narratives and engage with the messy, fascinating, often contradictory story of how we became who we are. Pack your curiosity and prepare to discover that American history is far more complex, more interesting, and more relevant than any textbook ever suggested.